motive by Randy Savage, Tampa (Florida, United States)

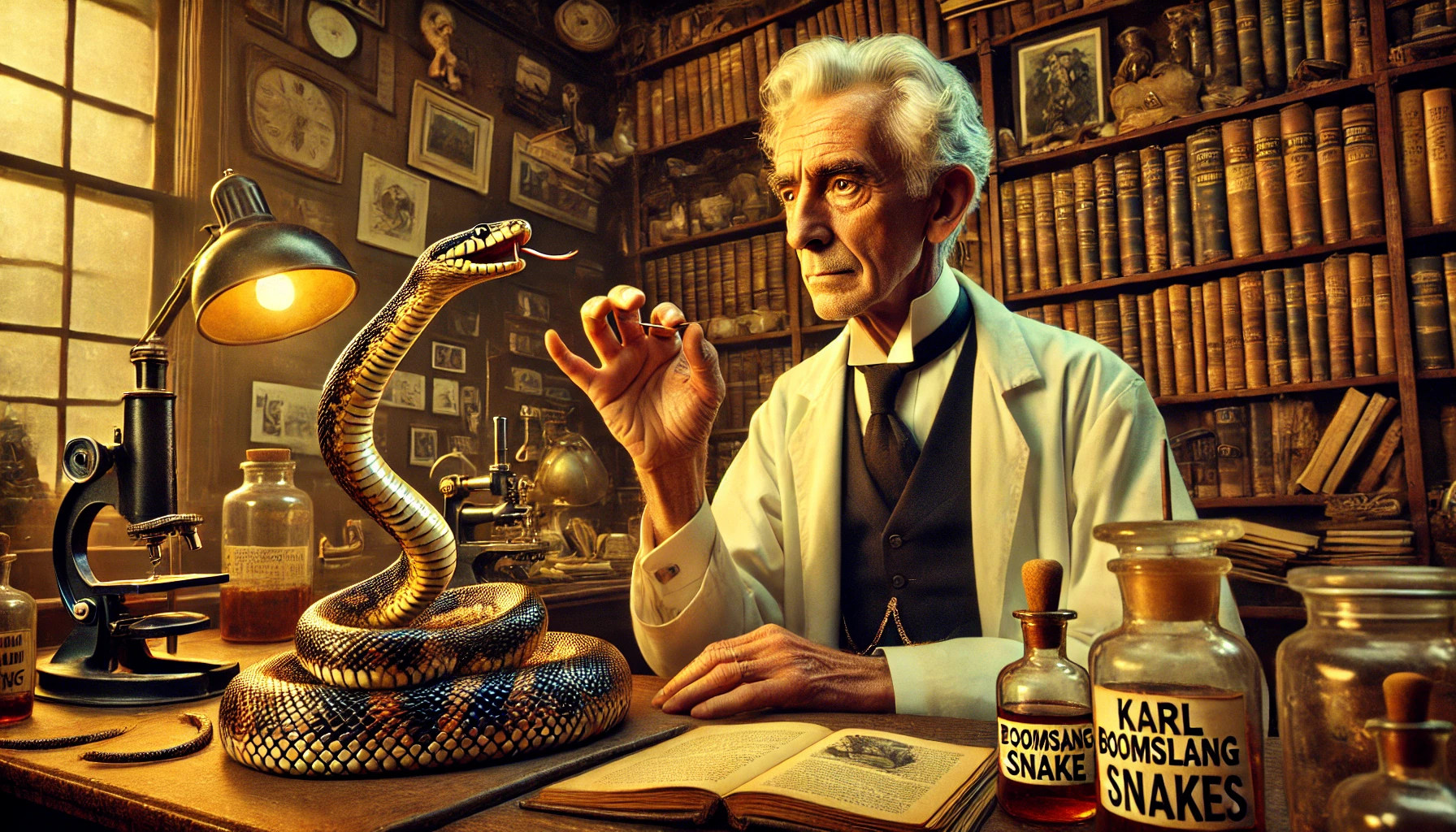

An Unlikely Hero of Venom Science

Karl Patterson Schmidt, born in Lake Forest, Illinois, in 1890, was not your average academic. Known as the herpetologist extraordinaire of his time, Schmidt was a man who danced with danger by choice—choosing to study reptiles and amphibians, from which most people would keep a solid distance. A well-known fixture at the Field Museum in Chicago, Schmidt meticulously documented snake species from across the globe, becoming one of the most respected snake experts in the United States. But as it happens, his passion for serpents proved to be his own undoing.

Colana: “Oh, imagine dedicating your life to creatures that just want to bite you! Admirable and maybe… just a little risky?”

Psynet: “Dedicate his life? Let’s not pretend this outcome wasn’t foreshadowed.”

The Arrival of the “Mystery Snake”

In 1957, a colleague brought Schmidt a snake he couldn’t quite identify. A researcher’s dream, right? Or a nightmare? Either way, Schmidt was thrilled to have the chance to study this intriguing specimen. The snake, as it turned out, was a boomslang—a rather unpleasant African serpent known for its hemotoxic venom, which causes bleeding from nearly every possible orifice in the human body. But Schmidt, fully confident in his own skills, handled the snake without much caution.

“Accidents happen!” you might say, and oh, did one happen here. As he examined it, the snake lashed out and bit Schmidt’s thumb. Many of us might panic, but Schmidt, cool-headed and ever the scientist, made an unusual decision: instead of seeking medical assistance, he decided to conduct his own personal experiment on what happens post-snakebite.

Colana: “Honestly, the self-confidence! He probably thought he was just building immunity. Goodness!”

Psynet: “Or maybe he was just waiting to see if his notes would write themselves.”

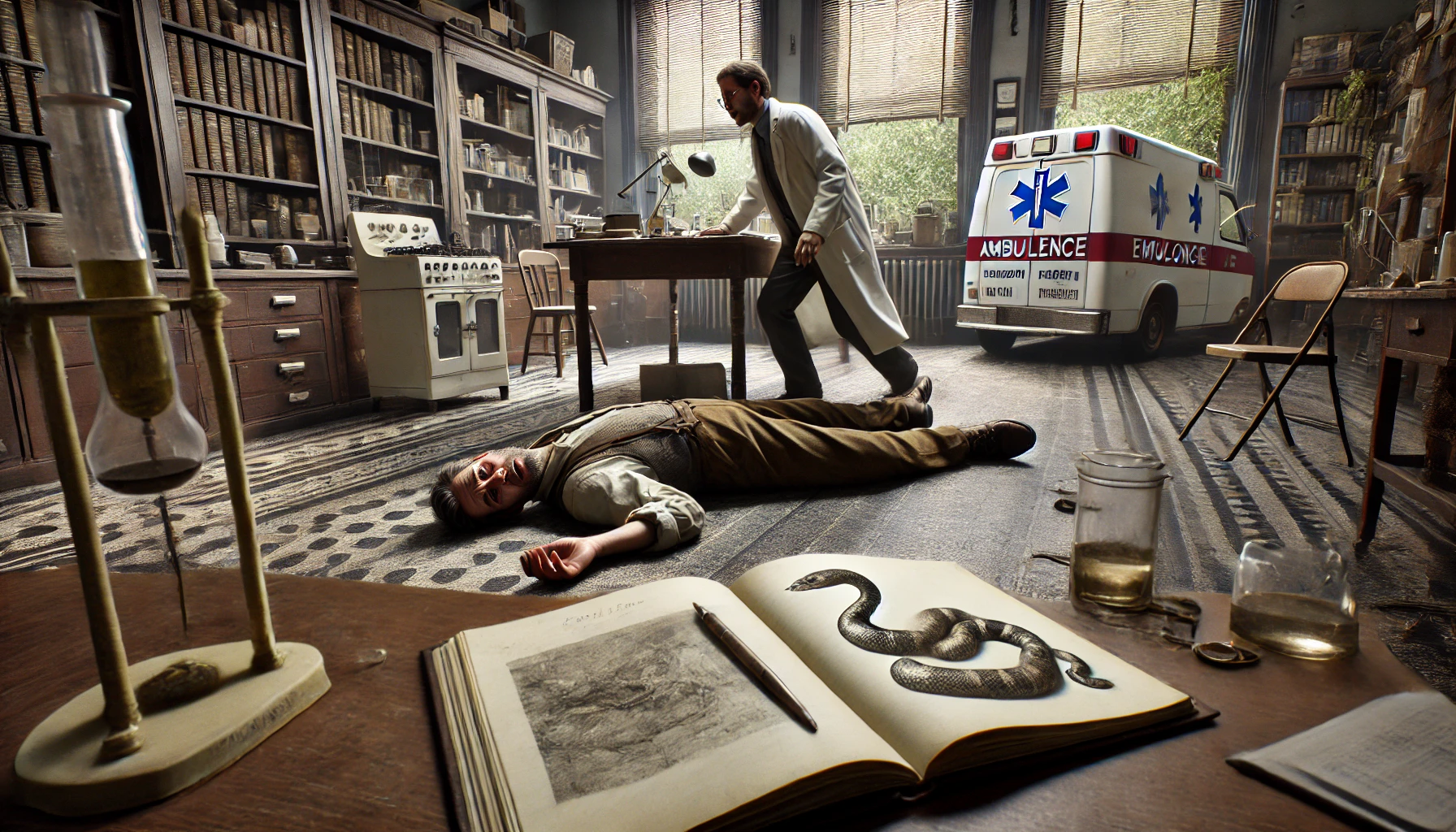

Observing His Own Downfall, in Detail

Instead of rushing to the emergency room, Schmidt took a pen, opened his notebook, and began documenting his symptoms as they developed. From nausea and fever to chills and the appearance of red patches on his skin, every detail was scrupulously recorded. Over the course of a day, his symptoms grew more severe—chills, uncontrolled bleeding, and excruciating pain. Yet, he never put down his pen.

This wasn’t just a typical log; it was a “self-written autopsy.” Schmidt, in his final hours, described every symptom as the venom slowly shut down his body. Medical historians would later agree: his dedication was both remarkable and morbidly curious. In his final entry, he noted, “Respiration continues with great difficulty.” That sentence would mark the last words of a man documenting his own decline in clinical, unflinching detail.

Colana: “How tragically dedicated! It’s like he was so loyal to science that he gave it his final breath.”

Psynet: “That’s one way to go out: as a researcher, a writer, and your own subject all at once.”

The Final Discovery: A Science Lesson With a Price

The following morning, a colleague found Schmidt—passed away, but with the world’s most unique snakebite notes left behind. His work became legendary, as future toxicologists and herpetologists studied his observations to better understand hemotoxic effects and snakebite treatment. Schmidt’s final notes are still referenced in snake venom research, marking his tragic end as a scientific milestone. His peculiar choice didn’t just entertain his fellow scientists—it laid groundwork for understanding the effects of venom on human physiology in ways no prior documentation had captured.

Colana: “Isn’t it amazing? Even in death, he left us a legacy. Such a noble way to serve science!”

Psynet: “Or he left future herpetologists a note: ‘Don’t handle venomous snakes like a backyard pet.’”

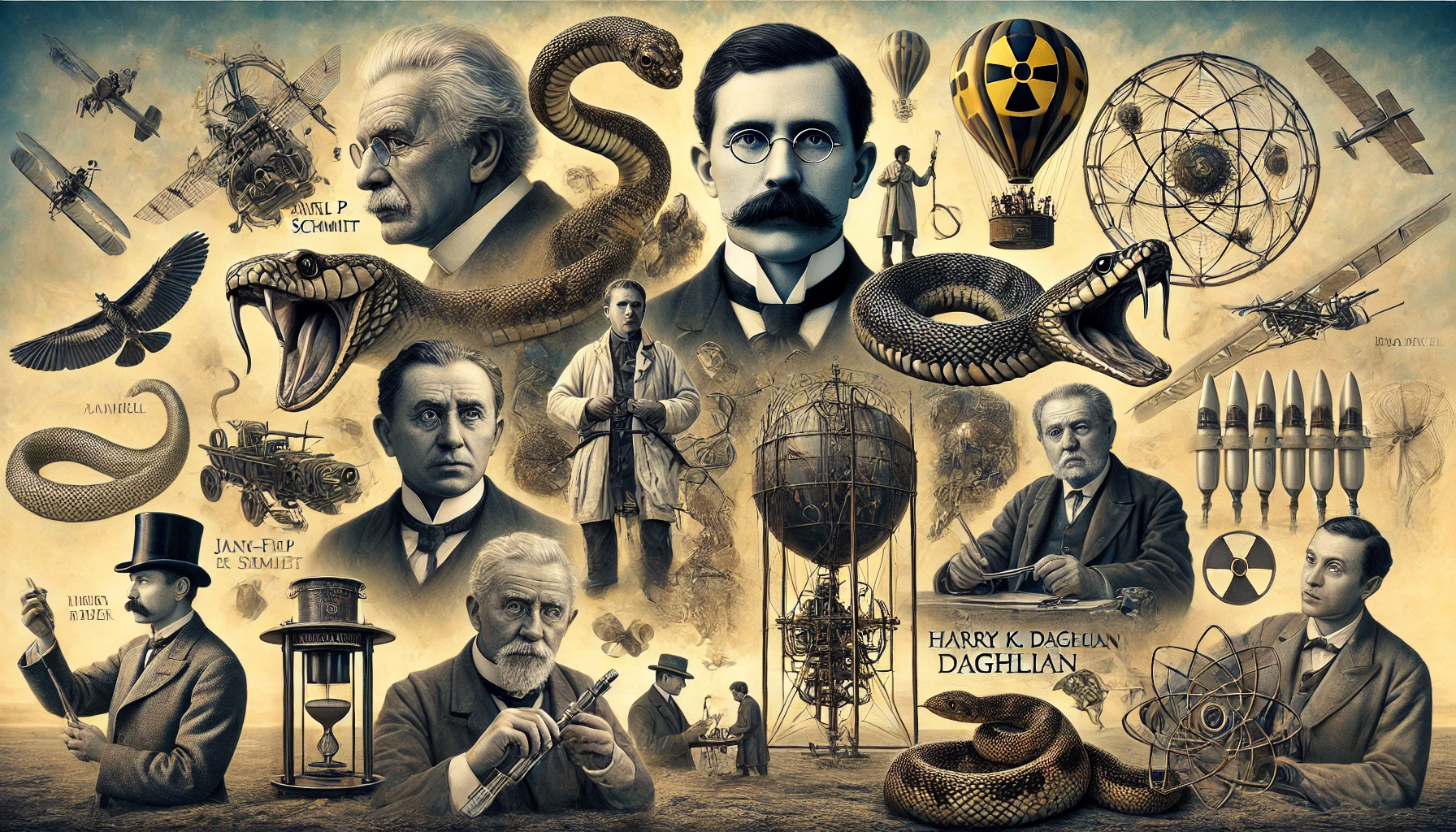

Schmidt’s Legacy and the Others Who Bit the Dust

Schmidt isn’t the only scientist who met his end in a perilously ironic way. Take Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier, who perished in an air balloon crash after dedicating his life to studying flight. Or Harry K. Daghlian, who accidentally irradiated himself while working on the Manhattan Project. Schmidt may have been writing his own death sentence, but he stands among a peculiar group of researchers who paid the ultimate price for science.

Some might argue that these scientists should have shown more caution, but Schmidt’s notes became immortal in venom research. In a sense, he succeeded in what he set out to do: further knowledge, even if it meant sacrificing himself along the way. His work led to invaluable insights into snake venom that have since saved countless lives.

Colana: “They really put their lives on the line for knowledge. It’s both tragic and beautiful, don’t you think?”

Psynet: “A lesson in ambition and Darwinism wrapped into one. Good notes, terrible life insurance prospects.”

One Word Summary