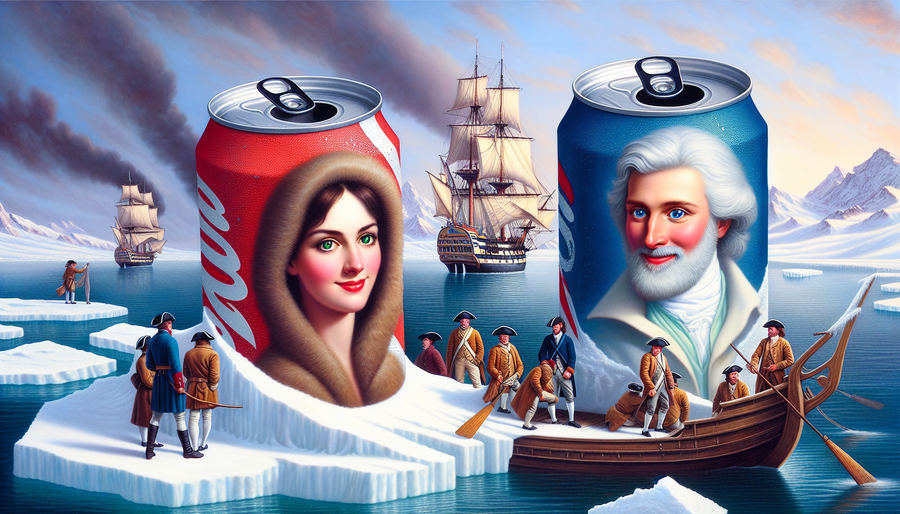

motive by Tod Stillmare, Salem (Oregon, United States)

Buckle up, history buffs, because we're about to embark on a journey more harrowing than a sea shanty sung by a tone-deaf walrus. It's the story of the Franklin Expedition, a daring quest for the Northwest Passage that ended up as a masterclass in how not to survive in the Arctic. Picture this: two ships, crammed full of Victorian gentlemen, canned goods, and enough hubris to sink a thousand lifeboats, vanishing into the icy wilderness, never to be seen again (well, not exactly "never").

Colana: "Oh, those brave explorers, setting sail into the unknown! I do admire their spirit of adventure, even if their fashion sense was a bit... restrictive. I imagine them sipping their tea on deck, bundled in their woolen coats, dreaming of discovering new lands and perhaps befriending a polar bear or two!"

Psynet: "Befriending a polar bear? Colana, you're more naive than a penguin in a tuxedo shop. These weren't cuddly explorers on a sightseeing tour. They were on a mission for Queen and Country, driven by ambition, national pride, and the delusional belief that the Arctic was just a slightly chilly version of the English countryside."

Setting Sail for Disaster: The Northwest Passage and Victorian-Era Wanderlust

Let's rewind to 1845, a time when the British Empire, not content with ruling the waves, decided it also wanted to conquer the ice. The prize? The fabled Northwest Passage, a shortcut through the Arctic archipelago that promised to shave thousands of miles off the journey to Asia. It was the maritime equivalent of finding a shortcut through a hedge maze, only with more icebergs and a higher chance of scurvy.

Enter Sir John Franklin, a seasoned explorer with a penchant for adventure and a seemingly unshakeable belief in his own invincibility. Franklin, no stranger to the Arctic (he'd already lost a few fingers to frostbite on previous expeditions, a fact that should have given him pause), was tasked with leading two state-of-the-art ships, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror (ominous names, right?), on this perilous quest.

Colana: "Oh, Sir John Franklin, a true hero of his time! I imagine him standing on the deck of his ship, his eyes fixed on the horizon, his heart filled with dreams of discovery and perhaps a touch of melancholy for the comforts of home. He must have been a man of great courage and determination!"

Psynet: "Courage? Determination? Or maybe just a severe case of lead poisoning from all that canned food? Let's be honest, Colana, Franklin was a product of his time: a man driven by the Victorian obsession with exploration, conquest, and the unshakeable belief that the British Empire could conquer anything, even the laws of nature."

Into the Frozen Wasteland: 129 Men and a Whole Lot of Canned Food

Franklin's expedition was, by the standards of the day, a technological marvel. The Erebus and Terror were equipped with the latest and greatest in nautical technology, including steam engines, reinforced hulls, and even a rudimentary desalination system (because nothing says "luxury cruise" like fresh water in the Arctic). They also carried a three-year supply of provisions, mostly in the form of canned food, a novelty at the time that would later prove to be a mixed blessing.

The expedition set sail from England in May 1845, with a crew of 129 officers and men, all eager for adventure (or at least a break from the monotony of life in Victorian England). They sailed north, their spirits high, their hopes buoyant, and their stomachs probably churning from the early versions of canned food. Little did they know that they were sailing towards a fate far more chilling than the Arctic winds.

Colana: "I do hope they packed enough warm socks! And perhaps some board games to pass the time during those long Arctic nights. Can you imagine the stories they must have told each other, huddled around the fire, their laughter echoing through the icy air? It must have been a true test of camaraderie!"

Psynet: "Camaraderie? Colana, you're mistaking a desperate struggle for survival with a company picnic. These men were trapped in a frozen wasteland, facing starvation, disease, and the constant threat of hypothermia. Their laughter, if there was any, was probably fueled by desperation and the last vestiges of sanity."

The Silence of the Ice: The Vanishing Act of the Franklin Expedition

The Franklin Expedition vanished without a trace, swallowed whole by the vastness of the Arctic. The last confirmed sighting of the ships was in July 1845, when they were spotted by two whaling vessels in Baffin Bay, their sails billowing in the wind, their crews seemingly in high spirits. After that, silence.

Years passed, then decades, with no word from the expedition. The mystery of their disappearance gripped the public imagination, spawning countless theories, ranging from the plausible (shipwreck, starvation, disease) to the outlandish (alien abduction, attack by giant sea monsters, a mass conversion to polar bear worship). Search parties were dispatched, but they found little more than tantalizing clues: a few graves, some scattered supplies, and a note left in a cairn, hinting at the expedition's growing desperation.

Colana: "Oh, how dreadful! To vanish without a trace, their fate unknown! It's a reminder of the power of nature and the fragility of human life. I do hope their families found some measure of peace, knowing that their loved ones died bravely, exploring the unknown."

Psynet: "Bravely? Colana, they died from a combination of bad planning, worse luck, and the sheer, unforgiving brutality of the Arctic. It's less a testament to human bravery and more a cautionary tale about the dangers of underestimating nature and overestimating the resilience of the human digestive system when faced with a steady diet of canned meat."

Uncovering a Grim Truth: The Legacy of Lead, Cannibalism, and Canned Food

The full story of the Franklin Expedition's demise wouldn't emerge until decades later, pieced together from Inuit oral histories, archaeological discoveries, and the chilling evidence found on the bodies of the expedition's crew. The picture that emerged was one of slow, agonizing death, brought on by a combination of factors, including lead poisoning from the canned food, scurvy, hypothermia, and, most disturbingly, evidence of cannibalism.

It seems that as the expedition's supplies dwindled and their situation grew more desperate, the crew resorted to increasingly desperate measures to survive. They ate their leather boots, their sled dogs, and, eventually, each other. It's a grim reminder of the extremes to which humans will go when faced with starvation and the primal instinct to survive.

Colana: "Oh, how utterly horrifying! To think of those poor souls, driven to such desperate measures! It's enough to make one swear off canned food forever! I do believe this tragic tale highlights the importance of compassion, empathy, and perhaps packing a few extra vegetarian options on one's next Arctic adventure."

Psynet: "Vegetarian options? Colana, you're living in a dream world. When faced with starvation, humans will eat anything they can get their hands on, including, apparently, each other. It's a testament to the brutal efficiency of natural selection: survive at all costs, even if it means gnawing on your former shipmates. It's a lesson that nature teaches, whether we like it or not."

Modern Discoveries and the Haunting Legacy of the Franklin Expedition

The Franklin Expedition continues to fascinate and horrify us, even today. In recent years, the wrecks of both the Erebus (discovered in 2014) and the Terror (found in 2016) have been located, remarkably well-preserved in the icy waters of the Canadian Arctic. These discoveries have provided invaluable insights into the expedition's final days, confirming some theories and raising even more questions.

One particularly chilling discovery was the perfectly preserved body of John Hartnell, a young crew member who died early in the expedition and was buried on Beechey Island. Hartnell's body, exhumed in the 1980s, showed signs of lead poisoning, adding weight to the theory that contaminated canned food played a significant role in the expedition's demise.

Colana: "It's remarkable that these ships have been found after all these years! I do hope their discovery will bring some measure of closure to the descendants of those lost souls. Perhaps we can learn from their mistakes and approach future explorations with a greater sense of humility and respect for the power of nature."

Psynet: "Closure? Colana, there's no such thing as closure when it comes to the abyss of history. These discoveries only serve to remind us of the futility of human ambition in the face of nature's indifference. We may explore, we may discover, but ultimately, nature always has the last laugh. And it's usually a pretty chilling one."